By Conrad Weiffenbach, Colombia Support Network, April 25, 2018

The delegation took place as the Colombian people and their government worked to implement the Peace Agreement [1] negotiated between The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the Colombian Government, for ending their destructive 50-year civil war [2]. The Peace Agreement provides a remarkable plan for Colombia’s future. At the time of writing this report, five months and a Colombian Congressional election have passed since November 2017. Political parties tending to oppose the Peace Agreement have won the most seats in the Colombian Congress, portending a future for Colombia that was only latent in our November 2017delegation experience. Presidential elections of mid-May, 2018 still lie in the future.

Participants:

Organizers: Jack Laun, attorney; Steve Bray, engineer; and Beatriz Vejerano, translator. Other participants: Eunice Gibson, attorney; Sarah Sasek, student f. State of Washington; Conrad Weiffenbach, physicist.

Informal Summary of the Peace Agreement:

- Comprehensive rural reform:

- free distribution of land to people without or with insufficient land.

- eradicating extreme poverty; reducing rural poverty by 50%.

- reducing overall inequality for populations within 10 years.

- programs dealing with hunger and malnutrition.

- measures to strengthen local and regional food production and markets. (all to be carried out by the Colombian Government)

- Rights and Guarantees for exercising political opposition by parties & movements. (to be carried out by the United Nations, FARC, etc.)

- Ceasefire, cessation of hostilities, and laying down of arms. (UN and FARC)

- National voluntary substitution for crops with illicit purposes. * (Government)

- For victims of the conflict: systems of truth, justice and reparation. (Government)

- Monitoring of implementation and verification of compliance. (United Nations)

(* In the Crop Substitution program [1], coca farmers are to have payments by the government equal to what they would have been paid for their coca, while instead they plant and grow food crops; and roads for transporting their new food crops to markets are to be constructed. This can be a sustainable way for Colombia to stop exporting cocaine without a need for spraying defoliants, and reduce rural criminality in Colombia substantially.)

Itinerary and Meetings of the CSN Delegation in Colombia:

Antioquia:

- Peace Community of San Jose de Apartado, Nov. 7 & 8.

- Coronel Antonio Jose Dangond Culzat, commander of army 17th brigade, Carepa, Nov. 8.

- Oscar Castano, Nov. 9, Medellin.

- Army Major General Jorge Arturo Salgado Restrepo, Commander of 17 th Division, Nov. 9, Medellin.

Putumayo:

Bogota:

- Rector Juan Carlos Henao; Universidad Externado de Colombia, Nov. 14.

- Francisco Ramirez; labor lawyer.

- Alirio Uribe Munoz, Chamber of Representatives

- Father Javier Giraldo, S.J., leading human rights advocate and founding patron of the Peace Community, CINEP; and William Rozo, director of CINEP’s data base.

- Ana Teresa Bernal; founder of the human rights organization Redepaz and head of the displaced persons office of the Bogota government under Gustavo Petro.

- Jahel Quiroga; attorney and human rights activist, Union Patriotica party.

- Rafael Pardo; Minister of Post Conflict in President Santos’ cabinet.

- Nancy Fiallo; human rights worker; monitors Colombian Supreme Court; supported the “Mothers of Soacha.”

- Todd Howland; UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in Colombia.

- Rodrigo Uprimny; University Professor, lawyer, writer about the Peace Agreement and transitional justice system.

- German Romero, attorney for the Peace Community.

- Marylen Serna Salinas; founder of the Campesino Movement of Cajibio, Cauca.

- Liz Ramirez; US AID, Democracy & Human Rights, at the US Embassy, Bogota.PEACE COMMUNITY

DETAILS OF DELEGATION MEETINGS AND ACTIVITIES IN COLOMBIA:

1. On November 8 th at the Peace Community [3] of San Josecito near Apartado, the CSN delegation met with Germán Graciano, one of the Community leaders, in their palm-thatched meeting space. He reported that they are still much beset by abuses, threats, and theft by paramilitaries.

German also said they had recently discovered that some “persons” are now acting secretly as informers and agents for “outside interests” associated with local enemies of the Peace Community. In CSN’s information from the Peace Community since the November 2017 delegation, the paramilitaries have continued harassing, threatening and even trying to control sub-populations within the community’s territory.

German also said they had recently discovered that some “persons” are now acting secretly as informers and agents for “outside interests” associated with local enemies of the Peace Community. In CSN’s information from the Peace Community since the November 2017 delegation, the paramilitaries have continued harassing, threatening and even trying to control sub-populations within the community’s territory.

For a comprehensive list of human rights abuses at the Peace Community from Jan. to June, 2017, see pp. 37-43 of ref. [4] Part of that list appears in the composite picture of Item #9 below (the meeting with Father Javier Giraldo S.J., a founding patron of the Community.)

2. In late afternoon of November eighth, the CSN delegation went to meet Colonel Antonio Jose Dangond Culzat, commander of army 17th brigade at his headquarters in Carepa, near Apartado. At the gate of the base we were told that Colonel Dangond was delayed by a big “drug bust,” and that Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos was visiting nearby on that occasion.

From newspapers [5] we later learned that twelve tons of high-purity cocaine had been confiscated from their underground hiding places in four different banana-growing fields near Carepa, and several low-level persons involved had been arrested.

On April 17 th 2017 Trump had met former Colombian presidents Álvaro Uribe and Andrés Pastrana at his Mar a Largo resort, unbeknown to the Colombian government [6] The president had been accepting little foreign policy advice from his State Department, but he may have received a view of the Peace Agreement from those former Colombian presidents who oppose it.

In September 2017, President Trump threatened [7] that if the Colombian cocaine trade was not interdicted, Colombia would be decertified as a partner in the (old) war on drugs and US funding would be cut. Apparently gone was consideration for the Peace Agreement, its crop- substitution program and other features to sustainably eliminate coca farming from Colombia.

It wasn’t long before Colombia responded: On October 5, eight unarmed coca farmers in a rural area near Tumaco were killed and many others injured by Colombian National police during a protest against the eradication of their coca crops and slow implementation of the crop substitution program (8, 9, 10.)

Then on November eighth President Santos came to Apartado to recognize and publicize the big cocaine bust.

Colonel Dangond finally arrived at his base in Carepa where the CSN delegation had been waiting for an hour or two. Because the 17 th Army Brigade serves a region including the Peace Community of Apartado, the delegation was pleased to have his attention. The colonel acknowledged he is held responsible for the safety of the Peace Community. He showed us a large clip-ring binder of reports on all the events regarding the Peace Community he has investigated since he began command of the brigade a couple of years ago, and he asserted he has found that the community’s versions of the events are all lies.

In response, the delegation reminded Colonel Dangond of proven army complicity in the massacre at Mulatos, February 21, 2005: Luis Eduardo Guerra-Guerra, one of the founders and leaders of the Peace Community, was murdered in an area near the Mulatos River and three children plus four other adults of the Community were massacred at the same time [7]. Then after a decision on that massacre was handed down from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, Colombian courts found several low-ranking officers of the 17 th Brigade guilty and they are now spending time in prison. Although higher-ranking officers responsible in the chain of command have been charged and the prosecution continues, none have yet been convicted.

3. In Medellin on the way back from Apartado, the delgation met with Oscar Castano, a well-known Colombian TV journalist and old friend of CSN, who long has been investigating and reporting on corruption in Colombia – most recently on the trafficking of women. The latter report has resulted in serious threats to his life, and he asked if CSN could help him get the government to continue his protection.

3. In Medellin on the way back from Apartado, the delgation met with Oscar Castano, a well-known Colombian TV journalist and old friend of CSN, who long has been investigating and reporting on corruption in Colombia – most recently on the trafficking of women. The latter report has resulted in serious threats to his life, and he asked if CSN could help him get the government to continue his protection.

Oscar Castano briefed the delegation about mysterious delays by certain Colombian government agencies in carrying out their responsibilities in the Peace Agreement. He speculated that various aspects of the implementation could favor one party or another in the national elections to come in March and May 2018. Moreover, if the parties supporting former Colombian president Alvaro Uribe (who opposes the peace agreement) win enough power, they would eliminate the Peace Agreement entirely from their government. Oscar Castano’s perspectives later helped us to understand much of what we were to hear in remaining delegation visits.

4. At his headquarters in Medellin the delegation met with Major General Jorge Salgado Restrepo, commander of the 7 th Army Division and reputed to have a bright future. He told us he believed the FARC had lost the military conflict. He also said (with no explanation) that troops under his command would be building rural roads. That road-building would fit with the program for facilitation of marketing new crops which campesinos have substituted for coca, but one could think supporting local contractors would be a better approach for building those roads.

5. On the afternoon of November 9 the delegation flew south to the Putumayo Department, fabled for beautiful forests, waterfalls and wildlife. We stayed the night in Mocoa, and the next day after visiting in the area we were driven in a truck through the Andes mountains on the infamous road to Sibundoy: 90 kilometers taking more than three hours of riding on dirt and gravel-surfaced switchbacks.

5. On the afternoon of November 9 the delegation flew south to the Putumayo Department, fabled for beautiful forests, waterfalls and wildlife. We stayed the night in Mocoa, and the next day after visiting in the area we were driven in a truck through the Andes mountains on the infamous road to Sibundoy: 90 kilometers taking more than three hours of riding on dirt and gravel-surfaced switchbacks.  In Sibundoy, the Kamentsa indigenous people invited our delegation to attend a meeting of leaders at their community offices. After many had spoken to their group about various concerns, a candle cermony followed.

In Sibundoy, the Kamentsa indigenous people invited our delegation to attend a meeting of leaders at their community offices. After many had spoken to their group about various concerns, a candle cermony followed.

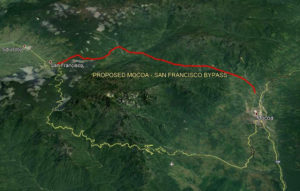

Before our drive to Sibundoy, outside of Mocoa we found some construction of the “San Francisco to Mocoa Variante,” which is of concern to the Kamentsa and other indigenous groups: This future superhighway passes through indigenous territory of sacred importance and facilitates exploitation of the land for mining and other development. Funded by the Inter-American Development Bank and the Colombian government, the construction runs west along the Mocoa River through high Andes to the Sibundoy valley, as part of a safer, faster route planned for heavy commercial traffic. However, we could see that construction had been halted for many months.

Before our drive to Sibundoy, outside of Mocoa we found some construction of the “San Francisco to Mocoa Variante,” which is of concern to the Kamentsa and other indigenous groups: This future superhighway passes through indigenous territory of sacred importance and facilitates exploitation of the land for mining and other development. Funded by the Inter-American Development Bank and the Colombian government, the construction runs west along the Mocoa River through high Andes to the Sibundoy valley, as part of a safer, faster route planned for heavy commercial traffic. However, we could see that construction had been halted for many months.

On the Google-Earth map view, next page, the current road from Mocoa to Sibundoy is indicated as a jagged yellow line at the bottom, and the planned “Variente” (in red) is part of a route from the Atlantic in Brasil, to Tumaco on the Pacific in Colombia.

On the Google-Earth map view, next page, the current road from Mocoa to Sibundoy is indicated as a jagged yellow line at the bottom, and the planned “Variente” (in red) is part of a route from the Atlantic in Brasil, to Tumaco on the Pacific in Colombia.  The bottom picture is from the current road, called the “trampoline of death.” The CSN delegation was driven that 90 km 3-hr trip both directions in a truck, through cleared landslides (one visible in picture,) and past sites with memorials where people had died in accidents.

The bottom picture is from the current road, called the “trampoline of death.” The CSN delegation was driven that 90 km 3-hr trip both directions in a truck, through cleared landslides (one visible in picture,) and past sites with memorials where people had died in accidents.

6. Flying back to Bogota, the delegation met with the chancellor of the Universidad Externado de Colombia, Juan Carlos Henao, also a former President of the Constitutional Court which helped draft the Transitional Justice plan in the Peace Agreement. Juan Carlos eloquently outlined for us the progress being made implementing the Peace Agreement, saying it was going essentially as envisioned; the Congress passing and courts approving legislation necessary for the government to act.

6. Flying back to Bogota, the delegation met with the chancellor of the Universidad Externado de Colombia, Juan Carlos Henao, also a former President of the Constitutional Court which helped draft the Transitional Justice plan in the Peace Agreement. Juan Carlos eloquently outlined for us the progress being made implementing the Peace Agreement, saying it was going essentially as envisioned; the Congress passing and courts approving legislation necessary for the government to act.

7. The delegation had lunch at the university with Francesco Ramirez Cuellar, a lawyer and defender of human rights well known for his work with labor unions (as discussed in Eunice Gibson’s contribution to this CSN Newsletter.)

8. Congressional Representative Alirio Uribe, of the Polo Democrático (opposition party), explained the politics of making laws through which the Peace Agreement may beadministered by the government. He outlined the pro- and anti-Peace Agreement political factions in the congressional and presidential elections coming March and May, 2018.

8. Congressional Representative Alirio Uribe, of the Polo Democrático (opposition party), explained the politics of making laws through which the Peace Agreement may beadministered by the government. He outlined the pro- and anti-Peace Agreement political factions in the congressional and presidential elections coming March and May, 2018.

9. The delegation met with Father Javier Giraldo, S.J., a leading human rights advocate and tireless defender of the Peace Community of San Jose de Apartado.  He is affiliated with the Center for Research and Popular Education (CINEP,) a Jesuit institution that catalogs the many human rights abuses of Colombian campesinos and others in an on-line report [4]

He is affiliated with the Center for Research and Popular Education (CINEP,) a Jesuit institution that catalogs the many human rights abuses of Colombian campesinos and others in an on-line report [4]

Fr. Giraldo repeated what we had already been hearing: that criminals are beginning to control the cocaine trade in areas which the FARC vacated when they demobilized, turned their weapons over to UN observers, and moved to the 26 rural veredas prepared for them. The criminals wanting to run the cocaine trade violently prevent campesinos from substituting other crops for coca [5] We also met with William Rozo, in charge of CINEP’s Data Base, who gave all six CSN delegation members (including Beatriz, our American-Colombian translator) copies of the large-format, 300-page CINEP paperback, Data Bank of Political violence and human rights in Colombia; Noche y Niebla for Jan.-June 2017 [4]

This huge and continuing cataloging of human right violations, which is also on the internet, provides one of the principal reasons why the rights of campesinos cannot be ignored by the Colombian Government, – which has agreed to the OAS Inter-American Convention on Human Rights, “Pact of San Jose, Costa Rica” [12]

10. We met with Ana Teresa Bernal, a founder of the human rights organization Redepaz and head of the displaced persons office of the Bogota government under Gustavo Petro. An old friend of CSN’s Cecilia Zarate, Ana Teresa seemed pleased to see Cecilia’s work continuing with high spirit in this delegation.

11. The delegation met with Jahel Quiroga, an attorney and human rights activist with the Union Patriotica. (Please see Eunice Gibson’s article in this Newsletter for a summary of the threats to Jahel and this political party, which continues work of the party from which so many electoral successes were achieved in local governments some thirty years ago. – Following which, thousands of elected local officials from the Union Patriotica were asassinated.)

11. The delegation met with Jahel Quiroga, an attorney and human rights activist with the Union Patriotica. (Please see Eunice Gibson’s article in this Newsletter for a summary of the threats to Jahel and this political party, which continues work of the party from which so many electoral successes were achieved in local governments some thirty years ago. – Following which, thousands of elected local officials from the Union Patriotica were asassinated.)

12. On November 15 in the Presidencia, Bogota, the delegation met with Rafael Pardo Rueda, Minister of Post-Conflict in Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos’ cabinet.  He was a student of Jack Laun’s some 40 years ago, in a class on urban policy at the Universidad de los Andes, Bogota. Rafael Pardo’s portfolio includes managing the expenses envisioned for implementation of the Peace Agreement.

He was a student of Jack Laun’s some 40 years ago, in a class on urban policy at the Universidad de los Andes, Bogota. Rafael Pardo’s portfolio includes managing the expenses envisioned for implementation of the Peace Agreement.

He mentioned six initiatives for the post-conflict government activity: 1) build 5,000 small (farm-to-market) roads in 15 years; 2) carry out a national land survey (catastral) program, at a cost of 7 billion dollars; 3) plans to modify and improve ruraleducational offerings; 4) carry out 1,200 small infrastructure projects in the next 6 months; 5) to remove land mines; and 6) to reduce the coca crop and improve removal techniques: to include reducing coca crop growing by 50,000 hectares this year, and providing coca farmers with $300 per month payments (about the same as they have been receiving for their coca production from those who buy the coca from them) for one year. He stated that the cost of these projects through the years would be $40 billion. What he did not tell us is when the funds for these projects would be released, or why more funds had not been released by his office to date.

13. We met with Nancy Fiallo, a human rights worker who monitors developments in the Colombian supreme court, and has suported the four “Mothers of Soacha” -of young men kidnapped, killed, and dressed as guerrillas, their bodies submitted to the Government for bounty, – in the army scandal known as the False Positives.

14. The delegation met with Todd Howland, UN High Comissioner to Colombia for Human Rights. He told us that per the Peace Agreement, a United Nations Mission was currently monitoring (among other things) reintegration of the FARC in the areas prepared for receiving them. He reported that the FARC had disarmed, demobilized and gone to their 26 assigned rural veredas. Then when allowed to leave, 75% did so, probably going to their homes or relatives. He said few had received the cash promised them in the Peace Agreement as debit cards for adjustment to their new lives.

14. The delegation met with Todd Howland, UN High Comissioner to Colombia for Human Rights. He told us that per the Peace Agreement, a United Nations Mission was currently monitoring (among other things) reintegration of the FARC in the areas prepared for receiving them. He reported that the FARC had disarmed, demobilized and gone to their 26 assigned rural veredas. Then when allowed to leave, 75% did so, probably going to their homes or relatives. He said few had received the cash promised them in the Peace Agreement as debit cards for adjustment to their new lives.

We asked about the possibility of a “plan B” to smooth the implementation of the peace agreements, in view of the problems we had heard so often about criminal groups having taken over the trafficking of cocaine grown in areas vacated by the demobilized FARC. Comissioner Howland pointed out that the planners of the agreement had contemplated using demobilised FARC, who could be quite effective helping the National Police and Army control criminals in their former areas, to enable the crop substitution program. However, that suggestion had been rejected during development of the Peace Agreements. Todd Howland has left Colombia since the CSN delegation met with him, ending his appointment as UN High Comissioner for Human Rights in Colombia.

The Annual Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the situation of human rights in Colombia for 2017 [13] is based on the work of Todd Howland and UN missions to Colombia for verifying and monitoring progress implementing the Peace Agreement. It’s an interesting, 20-page read of revealing detail, which:

“stresses the specific challenges in rural areas, including insecurity, violence linked to illicit economic activities in the context of disputes between illegal armed groups and organized crime, particularly in the areas of former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People’s Army influence.

The report also highlights the increasing attacks on human rights defenders, the impact of corruption on disparities in the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights, and the difficulties of addressing multi-dimensional, decades old problems suffered by the rural communities.”

15. Rodrigo Upprimy, one of the most prestigious legal minds in relation to the Peace Process, met with the delegation at Dejusticia, an office of lawyers. He gave the delegation a considered view of possible scenarios for elections and their impact on implementation of the Peace Agreement. Unfortunately, we now know the Colombian Congress will have more representatives from parties opposing the Peace Agreement than those favoring it, and the prospects for realizing the Peace Agreement in Colombia have diminished.

16. The attorney for the Peace Community, German Romero, met with the delegation to explain the current situation regarding titles to the Community’s land. This is a timely matter in view of the Peace Agreement’s ambition to sort out titles to land for campsinos. He presented a professional discussion of how differing laws affect the Peace Community’s claims to various parcels of the land they occupy.

17. The delegation met with Marylen Serna Salinas, a founder of the Campesino Movement of Cajibio, Cauca, and a national spokeswoman for campesino organizations.  Because of her effectiveness through the years, serious threats have been made to her person.

Because of her effectiveness through the years, serious threats have been made to her person.

Asked (as a metaphor) where she thought the campesinos might be in fifty years, after some discussion and based on her extensive experience organizing with them, Marylen said she “hoped they would be in the cities because there is simply far too little opportunity for them in their rural areas.”

18. At the US Embassy in Bogota, the delegation met with Liz Ramirez from US AID, Democracy and Human Rights. The question of how the US can help deal with problems implementing the crop substitution program was asked. She replied that the current strategy is “wholistic,” without explanation. This could imply throwing every asset at the problem, which might include sending 80,000 Colombian soldiers to the areas vacated by the FARC [14] where they could control the criminals who force coca growers out of the crop-substitution program.

The 2017 meeting of the CSN delegation at the US Embassy contrasts with the April, 2016 delegation meeting there, which was attended by the Human Rights Officer and five other staff working on the peace process. Then-President Obama had

“promised to throw the White House’s full support behind the Colombian government’s efforts to sign a historic peace agreement with leftist rebels, including a pledge of $450 million in aid annually to help demobilize rebels who’ve been fighting an insurgency for 51 years ” [15]

The embassy staff reported to that 2016 CSN delegation they were planning for a large amount of US aid to Colombia in support of the Peace Agreement. In March 2018, a $1.3 trillion bill funding the US Government was passed by Congress, and it includes $391 million in foreign aid for Colombia, which (before it passed) President Trump had been threatening to cut by $140 million [16]. That Congressional Republicans passed this legislation indicates support for peace-accord implementation, at least to Adam Isacson, of the NGO, Washington Office on Latin America [16]. However, Isacson’s New York Times op ed, Colombia’s Imperiled Transition [17] outlines several important factors now making implementation of the Peace Accord problematic, including that US funds cannot go to former FARC members. Nonetheless, most of the government’s responsibilities in the Peace Agreement involve programs for populations other than the FARC.

Conclusion:

If there is no US financial support for implementation of the Peace Agreement, or if a new administration not supporting it wins the Colombian elections in May, then there may be great disappointment among supporters of the Ageement, in Colombia and abroad. In either case, the Colombia Support Network plans to follow events closely and continue to accompany our friends, including the Peace Community of San Jose de Apartado, in their efforts for peaceful and sustainable development as near as possible to that envisioned in the Peace Agreement.

REFERENCES

- National Government of Colombia. Bogota, D.C., Colombia. (November 24, 2016). “Final Agreement to End the Armed Conflict and Build a Stable and Lasting Peace” (in English June 20, 2017). [http://especiales.presidencia.gov.co/Documents/20170620-dejacion-armas/acuerdos/acuerdo-final-ingles.pdf]

- Lisa Haugaard. (2014). Latin America Working Group. ” The Human Costs of the Colombian Conflict”. [ www.lawg.org/storage/documents/Col_Costs_fnl.pdf]

- Communidad de Paz de San Jose de Apartado. (2018). Colombia. [http://www.cdpsanjose.org/]

- Center For Popular Research and Education (CINEP). Banco de Datos de Derechos Humanos y Violencia Política. Bogota, D.C., Colombia. (September 29, 2017). “Revista Noche y Niebla No 55” pp 37-43. [http://www.nocheyniebla.org/]

- Reuters staff. (November 8, 2017). “Colombia seizes 12 tons of cocaine, its biggest ever haul”. [https://www.reuters.com/article/us-colombia-drugs/colombia-seizes-12-tons-of-cocaine-its-biggest-ever-haul-idUSKBN1D9005]

- Franco Ordoñez and Anita Kumar. Miami Herald. (April 20, 2017). “Secret meeting at Mar-a-Lago raises questions about Colombia peace and Trump”. [http://www.miamiherald.com/news/politics-government/article145805169.html]

- Reuters staff. (September 14, 2017). “Colombia defends anti-drug efforts after Trump critique”. [https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-colombia-drugs/colombia-defends-anti-drug-efforts-after-trump-critique-idUSKCN1BP1VV]

- Amnesty International. (October 6, 2017). “Colombia: The killing of peasant farmers in Tumaco underlines the need to implement the Peace Agreement”. [https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2017/10/colombia-asesinato-de-campesinos-en-tumaco-subraya-necesidad-de-implementar-el-acuerdo-de-paz/]

- Abby Martin. Telesur TV. (December 13, 2017). “The Colombian Government is Failing the Peace Deal”. [https://videosenglish.telesurtv.net/video/692879/abby-martin-the- colombian-govt-is-failing-the-peace-deal/]

- Sibylla Brodzinsky. The Guardian. (October 9, 2017). “Colombia suspends police officers who fired into crowd, leaving six dead.” [https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/09/colombia-suspends-four-police-officers-deaths-coca-farmers]

- Colombia Support Network. (June 26, 2005). “Massacre at Mulatos”. [http://colombiasupport.net/2005/6_26_rpt/san_jose_investigation.htm]

- Organization of American States. (November 22, 1969). “American Convention On Human Rights “Pact Of San Jose, Costa Rica” (B-32)”. [https://www.oas.org/dil/treaties_b-32_american_convention_on_human_rights.pdf]

- “Annual Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the situation of human rights in Colombia for 2017”. (March 2, 2018). [http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session37/Documents/A-HRC-37-3-Add_3_EN.docx]

- Reuters staff. (November 23, 2017). FARC dissidents face full-force of Colombia military: president. Reuters. [https://in.reuters.com/article/colombia-peace/farc-dissidents-face-full-force-of-colombia-military-president-idINKBN1DO084]

- Franco Ordoñez. Miami Herald. (Feb. 4, 2016). “White House seeks to boost aid to Colombia to $450 million”. [http://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/colombia/article58540593.html]

- Jack Norman. Colombia Reports. (March 23, 2018). [https://colombiareports.com/us-will-again-give-391m-in-aid-to-colombia-despite-trump-effort-at-cuts].

- Adam Isacson. New York Times. (April 5, 2018). “Colombia’s Imperiled Transition “. [https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/05/opinion/colombia-farc-transition.html]