By Juan Pablo Pérez B., La Silla Vacia (Colombia), January 21, 2019

Original article: https://lasillavacia.com/silla-caribe/la-alerta-en-el-salado-es-en-realidad-en-todo-montes-de-maria-69629

Translated by CSN volunteer Diana Méndez

A few days ago, the beleaguered and resilient El Salado district in Montes de Maria – site of one of the worst paramilitary massacres [in Colombian history] – was in the news again because of an alarm raised by journalist Daniel Samper Ospina about threats against social leaders and journalists there.

In some places, there was talk of up to a dozen threatened activists in this district, which is part of the municipality of Carmen de Bolivar.

We managed to confirm that there are two threatened activists in El Salado and that the alarm really applies to all of Montes de Maria, a region of 15 municipalities in [the departments of] Bolivar and Sucre. The war in the region ended over ten years ago, but there are still problems of conflict over land and because the area is a stop on drug trafficking routes.

These are basically the two issues that explain the threats and danger endured by social activists there.

The threatened leaders in El Salado

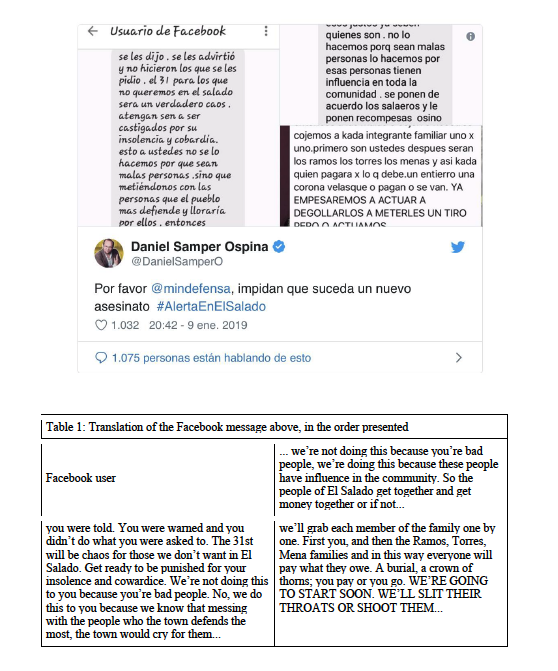

Daniel Samper tweeted the alarm on January 9th with the hashtag #AlertaEnElSalado [#AlertInElSalado], to signal its importance and grab the attention of the authorities.

[translated tweet: Please @mindefensa (Ministry of Defense), prevent another murder #AlertInElSalado]

Daniel Samper Ospina (@DanielSAmperO) January 10, 2019

After this, the prosecutor, Fernando Carrillo, requested the intervention of security forces and announced that a Roundtable for Life would be held on February 7th.

According to local leaders and functionaries, the people who were threatened

were two social leaders, Yirley Velasco and Leiner Ramos, both on January 9.

Velasco has been traveling for years through El Salado and other rural towns of Carmen de Bolivar, teaching women about their rights and assisting those women who have been victims of sexual violence in reporting their attacks.

She herself is a survivor of sexual violence that took place during a massacre in the town in February 2000, when 66 people were brutally killed.

Together with twelve other survivors, she created an organization named Mujeres Sembrando Vida [Women Sowing Life],

of which she is a legal representative and with whom she has been working for a

decade “in the struggle for the empowerment of women”.

Even though she had received several threats throughout the years, this last one was different since the death threats were not just for her but her entire family.

The messages arrived through WhatsApp and said that they would murder her and her entire family.

Lerner Ramos, the other threatened person, is El Salado’s Sports Coordinator

and has been recognized for his work with young people, who he teaches soccer

to keep them away from drug trafficking.

Ramos received the threats via Facebook. They said that time was up for him to leave the town, that he was out of “excuses”.

Even though only Velasco and Ramos

were directly threatened, one of the messages that Velasco received, which was

published by Daniel Samper, mentions the Ramos, Torres, and Mena families.

Two days after that, threats against two local journalists, who came to El Salado to cover the story, also came to light.

Journalists under threat

The day after that these denizens of El Salado received their threats, a journalistic team from Caracol Radio made up of Sebastian Bossa and Cristina Navarro, as well as their driver, Remberto Toro, went to the town to investigate the stories. That Thursday evening, after having travelled throughout the municipality conducting interviews and taking down accounts from people, two men on motorcycle yelled at them, saying, “Careful! They are going to kill you!” and kept on going. The reporters had to spend the night in the emergency response kiosk of the Colombian National Police in El Salado and leave the municipality the next day. Who carried out the threats and the reasons behind them are still unknown.

Following threats against leaders and journalists, on January 12 a security council was held in the district, attended by the governor of Bolívar, Dumek Turbay, and members of the Public Forces [National Police and Armed Forces]. There it was decided that 20 million pesos (US $6,417.00) would be given to anyone who provided information that could lead to the perpetrators of the threats. But the warning goes farther still, extending throughout [the region of] Montes de Maria.

Other threatened leaders

Last June, the Ombudsman’s Office issued a report warning about the threats received by members of the Mesa de Víctimas de El Carmen de Bolívar [Victims Roundtable of El Carmen de Bolívar] and members of the Movimiento Pacífico de Alta Montaña [Alta Montaña Peace Movement], who became aware of a plan to assassinate them. This past January 9, the Public Ministry also issued alerts about the threats received by social leaders in María la Baja. In this municipality on the Bolivar department’s side of Montes de María, peasants have been struggling for years for land and water, which are polluted by extensive palm cultivation. There, the Ombudsman said that, due to the collective demands for land, members of the Displaced Peoples’ Association of El Cucal have been intimidated by armed men. He also noted that other organizations, such as the Association of Community Councils of Montes de María and the Association of Afro-campesinos of María la Baja, are at risk. According to two reports from the Ombudsman’s Office, two reasons for threats against social leaders are the presence of the armed structures of the Golfo Clan, [which seeks] control of narco-trafficking routes, and conflict over land ownership. Both of these problems have been in Montes de María since before the war started and remain to this day.

Land: cause and effect of the war

In the 1970s, the Montes de María region was a major site of land reclamation by the National Association of Campesino Users [ANUC in Spanish].

According to a report by the Center for Historical Memory regarding the El Salado massacre, the event was a product of the erosion of the traditional plantation system, brought about by the agrarian reforms of the liberal governments of Alberto Lleras Camargo (1958-1962) and Carlos Lleras Restrepo (1966-1970). One of the measures that encouraged land reclamation was the creation of the Colombian Institute of the Agrarian Reformation (INCORA in Spanish), which was key for the transfer of land to farmers. Much of the land reclaimed by the campesinos in the 1970s has been abandoned after the reigniting of the war between guerrillas and paramilitaries in the 90s and 2000s.

Once the war ended – with the 2005 demobilization of the Heroes of María Block [of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, AUC, a paramilitary organization] and with the dismantling of FARC Fronts 35 and 37, after the death of the guerrilla leader Martin Caballero – the lands that had been abandoned have been occupied again.

However, as we [saw] in 2009, those who began to occupy [these lands] were not

the peasants who were displaced by the war and the massacres, but large

companies that made massive purchases of land. Thus, according to an article by

the researcher at the Technological University of Bolívar (UTB), Armando

Mercado Vega, entitled “Agrarian Counter-Reformation and Armed Conflict: Abandonment

and Dispossession of land in the Montes de María, 1996-2016”, what took place

in the region after the armed conflict was a process of agrarian

counter-reform. That a considerable part of the properties affected by agrarian

reform were the ones impacted by abandonment and forced dispossession implies

the possibility of agrarian counter-reform in the region, states the author.

In fact, according to a study by the Notary and Registry Superintendence of 2011, more than 50 percent of the lands purchased en masse after the end of the war in the Montes de María were properties that had been adjudicated by the then INCORA (today National Land Agency). In the Montes de María, since 2011, with the Victims and Land Restitution Law, a land restitution process began through which the peasants – who had been displaced from their homes during the years of the conflict and, upon returning, found their land belonging to a company or a landowner – are recovering their land. This, as stated by the Ombudsman’s Office in the alerts regarding Carmen de Bolívar and María la Baja, is evidence that the old conflict over land is back in the region.

The apparent normalization of public order in the municipality facilitated the resurgence of social processes of collective and community organization with the purpose of demanding from the State the administrative reparation of the land dispossessed during the hegemony of the AUC. This resurgence in the demand for the rights of the victims [has] led to the reactivation of the historic conflicts over land, says one of the alerts. “Today, there are very strong [social leaders], empowered by the Peace Agreement with the FARC, who are now more visible and that is why they are more at risk,” [researcher] Armando Mercado Vega explained.

As proof that the armed conflict over land is still alive and well in the Montes de María, on December 12, a [government] decision returned to three families (the Menas, the Martínez, and the Domínguez families) the properties from which they [had been] displaced after the El Salado massacre in February 2000. Strangely enough, one of the families threatened in the message received by social leader Yirley Velasco has the name Mena. According to an official who knows the area, [the threatened] family is the same [one that had benefitted from] the decision.

Narco-routes: the other problem

The other major structural problem in Montes de María is that the area has been, since before the war broke out between paramilitaries and guerrillas, a drug trafficking route. And so, even though there has not been cultivation or production of drugs, it remains key in the drug trafficking chain because it connects the Gulf of Morrosquillo, one of the sites for drug export in the Caribbean, with production sites such as Bajo Cauca, the south of Bolivar, and the Catatumbo region. This strategic location meant that, as an expert from the La Silla Caribe network, Luis Fernando Trejos explained, towards the late 1980s drug traffickers began buying properties in the area with the objective of exporting cocaine hydrochloride.

Currently, the area is controlled by the Golfo Clan, which, though lacking a large armed structure, has influence over [criminal] bands that it subcontracts locally. A department official and a local leader stated that, in El Salado and in several villages and towns throughout the Montes de María region, there is “micro-trafficking” and influence of criminal gangs. [Such small-scale, localized drug] trafficking has increased in rural areas. The notable thing is that the zone of influence and routes that [such organizations] use to get drugs out of the region are the same ones used by the paramilitaries 20 years ago, the official explained. For the Ombudsman, the presence of the Golfo Clan is one of the risk factors threatening the safety of the social leaders in the area.

The convergence of these two historical problems – conflicts over land and drug trafficking – are some of the reasons that explain the risks that social leaders live, not only in El Salado, but in all the Montes de María. [In this way,] the recent threat to social leaders in the region is not about the return of a conflict [that has been] absent for more than ten years to one of the areas where it was harshest. [Rather, the recent threat to social leaders symbolizes] that the problems that made that war possible never ended.